Fender designed and built more than one transitional, non reverb blackface combo amp that would soon acquire reverb and a new name, including relatively small numbers of blackface Princetons, 4×10 Concerts, 1×12 Vibrolux and 1×15 Pros. We acquired a 1×15 blackface Pro, and while it ultimately proved to be an extraordinary exceptional amp, we were also reminded of the potential pitfalls that exist when buying old amps sight-unseen, as well as the potential rewards.

We found the ’64 Pro listed on eBay and bout it from a dealer after requesting a detailed photo of the chassis and circuit. Proudly described as “the best amp in the store, “the rare ’64 blackface Pro is essentially a blackface Vibroverb without the “verb.” Do we have your attention yet? Three caps had been replaced, the original baffleboard had been professionally converted to plywood with the original grill cloth remaining intact, and an on/off pot had been installed for the tremolo intensity control that bypassed the tremolo circuit when rolled to “1” with a click, adding gain that would otherwise be missing in the Vibrato channel. We pulled the JJ power tubes and assorted Russian pre-amp tubes and replaced them with lightly used,“test new” RCAs from our stash, rebiased the amp and fired up the Pro….

Sounded like shit. We had been here before with a dead-mint ’64 Vibroverb bought years ago that had passed through a certain amp guru’s hands in Pflugerville, Texas.How could a vintage Fender sound so bad we wondered? Turned out that the value of the bright cap on the Vibrato channel had been changed on the Vibroverb, rendering a thin, scalding tone that would have given Ed Jahns fits, as it did us. Changing the bright cap back to spec immediately restored the Vibroverb to its rightful pace in history, but the Pro had other problems….

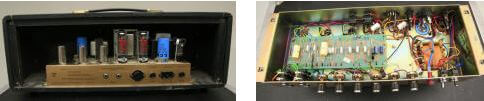

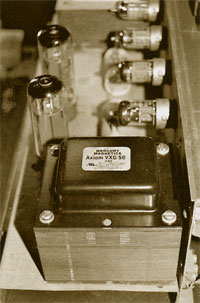

The baffleboard swap and added switch on the tremolo intensity control were clues that someone had also spent time troubleshooting the amp, probably trying to detect the cause of the Pro’s weak output, thin tone and curiously harsh edgy distortion. The amp just didn’t sound right. We pulled the original, reconed Jensen C15N dating to 1964 and subbed in an Eminence Legend, but the Pro still sounded choked-off, linear and wrong, so it was off to Jeff at Bakos Amp works on the Friday afternoon before Memorial Day weekend in a frog-chokin’ Georgia thunderstorm. When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro…..Now, this is the difference between someone who really knows his craft and a hack….Jeff plugged his bench guitar into the Pro, hit a couple of chords, issued a single grunt of displeasure and caustically observed, “Something is definitely fucked up.” With the chassis on the bench, Jeff scowled at the choppy sine wave the amp produced on his scope as he checked voltages with his multimeter. “I think the output transformer is going down slow—it measures 11 volts and it should be reading 16….” He clipped in a substitute OT from a stout old Fisher hi-fi, plugged in and hit a chord… “That’s closer to what it’s supposed to sound lie….” And sure enough, the missing lows and mids were present, the raspy treble tones were subdued, and for the moment, the Pro showed promise. We called Paul at Mercury Magnetics and ordered a black-face Pro Tone Clone replacement trans-former, shut it down and wished each other a good holiday. A week later the Mercury Magnetics replacement output transformer had arrived. Jeff wired it up, and then turned his attention o three silver mica caps that had replaced the original ceramic caps in the phase inverter and tone circuits. Jeff: “Somebody probably read an article about how these would bring the high end up, but I prefer the ceramics—always have. Besides the effect of the voltage from the old output transformer being low, these silver mica caps were contributing to that brittle tone we were hearing. They are the wrong value, and they changed the entire sound of the amp.” Jeff pulled all three silver mica caps and replaced them with the correct ceramic disc caps, and since an on/off switch had already been installed for the tremolo, we mounted the 25K mid range pot in the back panel hole for the extension speaker jack. With the Pro now thoroughly put right and the midrange pot added, Jeff hit a few chords, moved the EQ and volume settings around a bit in both channels, smiled and said, “That sounds really good. Yeah, that’s it.”

Back in our music room, the final step was to re-bias the Proat 34mA with an AmperexGZ34 rectifier and our last pair of vintage RCA black plate 6L6s, which in unused, new old stock condition have soared to $400/pair. The re-labeled Tube NOS Phillips JAN 6L6 WGBs we had tried sounded good—but the smooth warmth, exceptional musicality and deep harmonic content of the RCAs just can’t be beat, and it is a difference you can definitely hear. Smoke ’em if you got ’em….

We lit up the Pro with the ’63Fender Reverb unit and reverently smiled at the jaw-dropping tones pouring from the big Eminence Legend 15. Imagine the sound of a slightly kinder, warmer sounding 40 watt Super Reverb void of the sharp, penetrating treble presence that has sooften left our ears ringing for hours after a tumble with a blackface Super. The sound of the ’64 Pro is all Fender, with solid bass that doesn’t fall apart at high volume as the smaller blackface combos can,sweet, singing treble tones, and now… a mid range control that can gradually push the amp beyond its original, clear and liquid “scooped” mid range voice to an exceptionally thick, “mid-Atlantic” roar that unleashes heavy sustain and rich, musical distortion as only a Fender can. The Pro brilliantly complements every guitar we own, producing the essence of classic Stratocaster, Tele, P90 and humbucker tones with clarity, depth and lush fidelity that literally fills the room. Yes, there are different and equally worthy tones to be had from the British classics,but we have never heard a more beautiful sounding or versatile Fender amp—one that can range from crystalline, blackface clarity to the full burn of an early blonde Fender Bassman at much friendlier volume levels. The Pro can get plenty loud, but it’s a loud that doesn’t kill you in the style of a Showman, Twin or a Super Reverb.

The irony in this unexpected discovery has not escaped us,and perhaps the weight of it is now becoming clear to you, too. This project did not begin well, and we confess to experiencing some remorse when the Pro arrived with a few bad mods, weak and thin from the original output transformer going down, and generally just sounding very wrong. Our dismay was soon displaced by genuine enthusiasm; however, as we were reminded that this is indeed what the quest for tone is all about it. We’ve acquired absolutely bone stock amps in perfect working condition that just couldn’t tote the note, so why should we expect to buy a 44 year old amp that’s been played without it needing a little repair and restoration work? The end entirely justifies the means.

Having finally experienced the Pro’s singular, exceptional sound, we wondered what had caused it to be relegated to such obscurity among all the Fender black face amps. Like the Vibrasonic and Vibroverb, perhaps it was doomed by the presence of the single 15” speaker. Like the Pro, the blackface Vibroverb 1×15 was produced for less than a year, and with the introduction of the 2x12Pro Reverb in 1965, Fender would no longer produce a 1×15 combo until the introduction of the silver face Vibrosonic in 1972. Yet, the earlier 1×16 Pros had been Fender’s flagship amps during much of the tweed era, and in 1960 the 1×15 brown Pro ranked second only to the1x16 Vibrasonic in the Fender catalog. Somewhere along the way, the 1×15 combo had clearly fallen out of favor with Fender, guitarists, or both, and given the short life span of the Vibroverb, even the addition of reverb couldn’t save it.

Twenty years later, Stevie Ray Vaughan elevated the Vibroverb to hall of fame status, otherwise, the 1×15 com-bos seem to have been perceived as “uncool” for anything bug jazz and blues, as if wearing a jacket and tie were required to play them. The Pro is a great blues amp, but it’s also a great rocker, and equally well-suited for jazz, pop and country. With far more clean head room and power than any tweed Pro and much stronger distortion, sustain and dynamic character than a brown Pro, the blackface Pro reflects Fender’s ongoing pursuit of more powerful, cleaner sounding amps, but unlike the black face Bandmaster, Tremolux and Showman, and Pro can really rock the house cranked. We suspect it’s a single 15 and missing ’verb that throws people off today, yet in’64 Pro shares its DNA with the ’64 Bassman and all the highly prized blackface combo amps, including the Deluxe Reverb, Vibrolux Reverb, Super Reverb and the heavily prized and hyped Vibroverb.

The contrast between the Vibroverb’s Holy Grail status versus the lowly blackface Pro simply underscores how easily we can be blown off course by what isn’t hyped on the Internet or in print, and by the powerful logic that suggests if anything 44 years old is truly noteworthy, “we” would already know about it. Well, apparently “they” don’t. But you do. Blackface Pros can be found for $1 500–$2,000,with originality and overall condition driving prices accordingly. Like the Deluxe, we wouldn’t buy one that has had all the blue molded capacitors or Allen-Bradley resistors replaced, but the transformers available today from Mercury will sound every bit as good or better than the originals, and as we have said so many times in the past,the Eminence Legend 15 is spectacular. Add some good,current production or NOS tubes and you will have been delivered to a place well beyond the common man’s limp and shriveled imagination. Now Quest forth….

In late 2009 I had the opportunity to talk with Sergio Hamernik about the history of the Mercury Magnetics, how he became involved in making transformers for guitar amplifiers, and the difference a high quality transformer can make on your tone.

How did Mercury get its start?

The company’s roots date back to the early ’50s. Mercury was started by an old General Electrics transformer engineer who was working there pre-World War II. He then went on to do a bunch of design work for the war effort. And in the early ’50s, hung a shingle and became self-employed.

The name “Mercury” came out of his passion for Mercury cars, he always drove a Mercury since the late ’40s — he loved those cars — and eventually moved from the East Coast to the West Coast where he found that there was a lot of military and aerospace work. A booming economy in the early ’50s gave him a lot of business.

I met him in the 1970s when I was an engineering student and an audio enthusiast. Back then the electronics world was well into its solid-state “evolution,” and interest in tube gear was quickly disappearing. Not for me, however. I found myself in demand as a guy who knew about those “old things”; not only the math, formulas and specifications but I also had the “ears.” I could fix and keep the old gear running. So, I worked as a hired gun for a bunch of studio heads and pro musicians.

Typically when an amp’s output transformer blew. No one seemed to know any better so it was just swapped by whatever “factory” replacement or an off-the-shelf “equivalent” catalog transformer was handy. The invariable result was that the amp’s characteristic sound was gone. And no matter what resistors, caps or tubes were used, it could not be rescued or returned to its original sound. It was the transformers, it turned out, that were the key. The problem was coming up with a way to remedy the blown transformer replacement or repair that wouldn’t alter its tone.

To further complicate things, most transformer people I dealt with just didn’t want to bother with the music industry. For the most part the established electronics industry considered the needs and opinions of the audio and MI (Music Industry) communities as subjective, run by kooks, and occupied by people who didn’t know what they are doing. Audio and MI had always been considered the illegitimate stepchildren to the rest of the industry.

Out of pure necessity I had to got involved with transformer design and manufacture. As a customer of Mercury, they had built many custom transformers to my specifications — although we had many heated, on-going debates on the subject because the company owner hated audio! He never did understand what made guitar amp transformers tick, or how musicians thought and reacted to them.

That aside, he pestered me for almost a decade to take over the company because he felt I was the only one qualified. Eventually I did, and that was when Mercury got serious about the guitar amp connection. Sometimes you end up becoming an expert at something when no one else wants to do the job.

By the time I took the helm we were developing a really good and workable understanding of the relationship of transformer design to decent tone and how amps should behave. And around 1980 we began the long and arduous task of collecting and cataloging transformer specifications for every vintage amp, from all over the world. The deeper we dug, the more apparent it became that there were all kinds of factors that no one had previously suspected that affected guitar tone. And likewise, no one seemed to be paying attention to such things.

In turn, we invented proprietary technologies to aid this work. Even after three decades, we’re still innovating and discovering new things. From that fundamental research came our now famous ToneClone series, and later the Axiom line, which is probably the most significant advancement in toneful guitar amp transformer designs since the ’50s. Both product lines, we’re proud to say, have distinctly different niches in the annals of guitar amp tone.

We’ve not only cured the old transformer tone issues, but made it possible for musicians to upgrade their existing amps. And we’ve also made it possible for amp builders to reproduce amps of the same or better grade than even the most outstanding vintage amps of the past.

When did you become involved with making transformers for guitar amplifiers?

Back in the ’70s I worked for people on a one-to-one basis, usually under confidential arrangements, with certain rock stars that just didn’t want to be bothered by their names being flaunted around. What they want was their amps running right for recording, projects, touring, etc.

The problem was that when technicians would fix the amps they’d often loose their tone. It turned out that the culprit was the replaced output transformers. A changed output transformer would completely alter the character of the amplifier. So as I was the guy doing most of the work to resolve this issue, this expertise was brought to Mercury where we began a special division to cater to the guitar heroes.

Word got around rather quickly that Mercury was able to repair, rewind, and restore the original transformers and it just grew from there. The whole “Tone Clone” thing came from artists who had these amazing irreplaceable amps, amps that often made recording history. They didn’t want to take these amps on tour. So we came up with the innovative idea of cloning their original transformers that they’d fallen in love with. With the clones we could now easily make, for the first time ever, several identical amps for them. Or they would assign their techs to drop-in the cloned transformers so they would have, for example, six amps that would all sound the same as that first perfect amp.

These artists could now go on tour and not worry about breakdowns or theft, and keep their prized-originals back at home.

I worked with Ken Fisher, the whole Trainwreck thing, and a lot of the early boutique guys — and still do with Alexander Dumble. They preferred to keep things confidential and not let too many people know who their sources were because there were so few transformer designers that catered to the guitar amp market.

There was also a slow-but-steady dumbing-down occurring in audio and all that had been the post World War II momentum. Many of the ex-military components we’d been using were high tolerance parts, with mil-spec formulations of iron and copper and so on, that had been used to win the war effort. During the ’50s and ’60s we enjoyed the benefits of those high quality components at surplus prices. But by the late ’70s, and definitely in the ’80s, steel manufacturers started to change recipes to make the iron and other materials much more affordable.

You can hear the differences between a late ’60s Marshall, a late ’80s Marshall, and a Marshall today. A good listen will really help you to understand what changes took place. Unfortunately they made so many of those changes more out of economic considerations than anything else. The amps were loud but they seemed to be losing sight of the fact that their tone was disappearing — the “recipes” had been changed.

In addition to many other factors, the iron that Mercury uses is custom-formulated specifically for us. We buy enough of it to be able to dictate the exact recipe from the foundries. And all of our iron is literally from American ore processed right here in the USA. 100% American made to the original specs. Are there drawbacks? Well, some of the iron rusts more easily, but that’s actually a good thing because rust is a natural insulator. But the opposite is also true. When you see a modern transformer with a silvery or a shiny core just know that they aren’t worth a damn when it comes to tone.

Can you tell us more about guitar amp transformer history?

Here’s an amusing anecdote that may help explain our case for guitar amp transformers: There’s a great deal of documentation, from back in the mid-’50s, where engineers, and other technical people, were writing really scathing reports on how awful the transformers were in the audio industry. Those darn transformers! When tubes were plugged into them there was a tendency to distort! And they couldn’t have any of that! Likewise with harmonic distortion — especially even-order harmonic distortion.

Many amp builders, techs and players, today, don’t understand that tubes were originally designed to run dead clean, linear, and be efficient voltage amplifiers. That the tone we’ve all come to know and love is caused by the transformers literally “irritating” the tubes into distortion.

Which is, of course, the whole point of what we are looking for in guitar amps. Back in the ’50s, they were fighting to get rid of those nasty distortion tonal characteristics. Now we embrace them. But that was audio – guitar amps were still in they’re infancy and yet to be realized. It took a generation or two of innovative musicians to take those “undesirable” tonal characteristics and create music; to work with distortion and make it into something musical.

Ironically, it was that no-distortion engineering mindset that ushered in solid-state, and why it was so openly embraced in the ’60s. It was solid-state electronics that eliminated the output transformer.

In the late ’60s, Vox went to Thomas Organ to have solid-state amps built. They were very proud of this state-of-the-art amplifier. Curiously, I met a few of the musicians from the late ’60s that were sponsored by, and using, those amps. The tone was so awful and unbearable that they used the enclosures but hid their old tube gear inside! As you may already be aware, the vacuum tube industry is alive and well, and we’re still waiting for the solid-state industry to catch up.

Part of the confusion is that musicians assume it’s the tubes that give them their tone. There’s a lot of synergy going on in an amp, and the tubes certainly contribute, but let me illustrate this another way. Did you know that there is what we call “output transformer-less” amplifiers in the HiFi world?

These amps basically parallel a bunch of power tubes together until they get down to 16, 8, or 4 ohms. There is no output transformer, so you literally connect the speaker directly to the tubes. If you ever get the opportunity to do an audio demo with this style of amp, you will find that while it works, it sounds nearly solid-state. The output transformer is what provokes a tube into giving the characteristics that we find desirable as far as tone. Audio engineers didn’t want the tubes to distort, as tubes are basically nothing more than very clean voltage amplifiers. But when you have a reactive element like a transformer, you irritate the tubes into harmonic distortion.

Therefore, the difference between a good and mediocre transformer is based on how it works and syncs with these tubes to produce the kind of tone or distortion we are looking for. It is not as easy as winding some wire around a steel core, if it was then we would not be having this conversation.

How does a Mercury transformer made today compare to the transformers made in the golden age of amps (the ’50s and early ’60s)?

One of the biggest mistakes existing in today’s amplifier community, especially amongst hobbyists and do-it-yourselfers, is to blindly copy every aspect of a vintage amplifier hoping to get a piece of that golden tone. At best, this method still produces very random results. One of the key reasons for this is the often-overlooked missing transformer formula. A builder will fuss around with the tiniest of other details but completely miss how the transformers fit into the equation. In short, get the transformers right, then the rest is much easier. Here’s another look at theses deceptively simple devices:

For vintage-style transformers, Mercury starts by duplicating the transformer design, build errors and all. We use the best grade components like they did in the ’50s and ’60s. We wind every layer and every turn as if it were a circuit in itself. In fact, the diagram on the left shows an output transformer circuit equivalent. Most people would think it is an audio circuit. These things are fairly complex, and all the numbers have to be right in order to get the tone we want as musicians.

We really do follow the recipe to a point. Although we don’t repeat any of the mistakes or inconsistencies that were prevalent, but didn’t affect tone. For example, if you were into Fender tweeds or late-’60s Marshalls. To do this we would literally put the word out to rent or borrow dozens of amplifiers to find the one or two that had the sound, and dismiss the rest. There were typically many inconsistencies as well as “happy accidents” in the best-sounding examples we’ve auditioned. A lot of this has to do with the sloppy tolerances of the original transformers.

For our transformers we extract the best parts and virtues of the original best-of-breed transformers and remove all of the obstacles to tone. Perhaps just as important is that we adopted a “cost is no object” approach, making our transformers equal or better than the originals — and then add consistency. We now have this so finely tuned that if you bought a transformer from us five years ago, and then the same one today, it would sound exactly the same. You don’t want good batches and bad batches, which is precisely what made the original production runs vary so much.

Another issue is the so-called controversy between paper tubes and nylon bobbins. In the vintage years they used both. Some people think that somehow, some magical quality comes from using a paper tube winding form over a nylon bobbin. Tonally it made no difference at all. Paper tubes were widely out of tolerance most of the time because of how they were made. They would wind multiple coils on long sticks then use a saw or blade to cut off the various coils. In order for these long tubes or coils to come off of their winding forms they had to be conical. So this invariably meant that the first coil would be larger in diameter and the last coils smaller. As you can see, it’s easy to see why each of these inconsistently-made bobbins had a greater difference than the material they were made from. And there are other issues that occur over time, like paper has a tendency to disintegrate, collect moisture, etc.

When we switched to using nylon bobbins the tolerances were within 3,000’s of an inch of each other, as opposed to the wildly varying amounts found in paper tubes. If you were ever to take apart a really old transformer (pre-’70s) sometimes you’ll find wood wedges that are jammed between the paper tube and the core because that piece of paper was too wide and too sloppy to fit into the core correctly! They would force a wedge in there so the darn things wouldn’t rattle!

Which method, paper or nylon, made for the best tone? It’s the luck of the draw. We’re fortunate in that we have all these stars as clients who have these amazing-sounding amps. They went through the hassle of culling and choosing and picking the special amps that inspired them. The amps they recorded with. When we analyzed their transformers we sometimes found happy accidents or other little anomalies that would set a transformer apart from already sloppy tolerances of the standard production run.

There are little subtleties and changes from one transformer to another that make a heck of a difference tonally. So when you look online at our list of ToneClones, just know that they are from the hand-picked, best-of-the-best amps of their model and era. We continue this “weeding” process every day — and there’s apparently no end in sight. And that’s why, with some amps, we have several versions — each with its own tonal qualities — and others only a single set to choose from.

We use this process to establish new benchmarks. And you never know, tomorrow a new variant may arrive that totally blows away what we already thought was as good as it could ever get.

It is interesting that you take that approach to upgrading — the never-ending search for better-sounding benchmarks.

There is no real money or glamour in what we do, it is really all born of a passion for music. I come from a musical family, my Mom taught me as a little kid that music was a form of “food.” And that hasn’t changed. Everyone who works at Mercury is just in love with playing and listening to music, and we all believe that there is always some room for improvement or a way to raise the bar somehow.

Back in the ’70s and ’80s there wasn’t really a need for a company that designed and sold transformers to the public, so I stayed away from the general public for as long as I could and really only worked with professionals.

But at some point I realized that it was the average player who was getting ripped-off. Things were getting dumbed-down, the tone is slowly and steadily being vacuumed out of the amps. They were becoming duller-sounding, less interesting and more noisy. So, we decided to formally launch this product line so the average guy could have access to our technology. It takes an extreme amount of labor and effort it takes to build them to this standard. You know, even if someone wanted to buy 1000 transformers we would have to no-bid them because we really don’t have any way of doing things quickly.

Automation isn’t a practical solution. Everything we do is wound by hand, one at a time; it is the only way it can be done. Say you have 100 turns and 10 layers, well that would mean 10 turns per layer — that is how a machine would think of it. But what if a rock legend’s best transformer was 9 turns on one layer, 11 turns on the next, 7 on the next, 3 after that and so on, but the sum total ended up being 100 turns. Sometimes one layer can have a different winding style than the other; sometimes it is non-symmetrical meaning, if it is a push-pull, that one side of the primary doesn’t have the same turns as the other side. If that was the recipe that created the magic, we’d have to duplicate it. It’s just not practical to build machines to do that, so we end up having to do it by hand. It’s the proud old-school craftsmanship way of doing things. Something I think we could see a lot more these days.

We have a reputation for nailing tone. Our Fender transformers don’t sound like Marshalls, they sound like Fenders — and vice versa. In fact, we’ve become the industry’s new standard. If you were going to design or create a tube-based amp, it’s clear that we’re the folks to talk to.

Can you explain how a Mercury transformer can improve an amplifier’s tone and how they outperform the stock transformers found in most amplifiers?

In designing toneful transformers specifically for guitars (and that’s all we’re talking about here, not necessarily transformers for HiFi or any other purpose), the trick is in the magnetic field and how it behaves. The nature and the speed with which the iron reacts to the changing of an alternating current, in an alternating magnetic field, is what makes tone happen.

If you have “slow” iron, you’ll have a dull, non-sparkly sound with no bell tones — no matter what you do with the amp it will always be kind of noisy and fuzzy.

Where others have tried and failed they’ve blindly followed generic transformer formulas without understanding that guitar amps are different animals. They’ve somehow missed that point despite all the evidence to the contrary. The fact is that transformers for guitar amps do not necessarily follow textbook rules.

Indeed, it should probably be noted that we’ve developed a whole new technology around transformer design specifically, and only for the guitar industry. And that these designs are essentially irrelevant to any other use. But Mercury is also in a highly unusual position. Our decades of transformer “vivisection” have revealed all manner of unconventional tips ‘n tricks to us. And we’re now the keepers of this new, but proprietary, technology.

I seriously doubt that we could have done it without the, let’s call it “archeological benefits,” of our observations. Decades of studying the good, the bad and the ugly of guitar amp transformers have revealed a great deal.

Nothing that I have found in the reissue market, transformer-wise, even resembles anything that was made during the “the golden age of tone.” They are unrelated. The inductance, magnetic fields — all of that is just completely different and far removed from the original designs and recipes. So there is no way that a reissue amp is ever going to sound vintage unless they bother putting in the right ingredients.

With our Upgrade Kits, for example we’re trying to show people that we can move forward into new sonic territory from where vintage designs and tone left off. And our Axiom series transformers are the definitive showcase for this technology. Their tone is just amazing.

To push the point even further, we don’t include any “voodoo” parts in our Upgrade Kits. With the exception of the transformers, the Kits use only common, everyday, and off-the-shelf components. And most of our Kits also include a Mini-Choke. When the circuitry is correctly designed a Mini-Choke will make a huge improvement in an amp’s tone because, in terms of its power supply, it changes the way the amp works.

A good guitar amp is only as good as its power supply. If you have a dynamic and moving power supply that reacts to the demands of the audio end you’ll get get great note separation and good bass dynamics. You start to hear chimes and other phenomenon, and even the harmonics between the strings like a “5th note.” What the heck is the “5th note”? In barbershop quartets, if they get their harmonies right, they hear the “5th note” which is basically a harmonic of all four singers. We are doing that with our guitars thanks to distorted amplifiers.

Where did the idea for offering an Upgrade Kit for amplifiers like the Champ “600” and Valve Jr. come from and who designed the Upgrade?

I designed all of the magnetics (the transformers and Mini-Choke) and the general concept behind the Upgrade in league with Allen Cyr from the Amp Exchange. He is one of the most competent, finest amp designers I know of; there are only about five in the world that are true masters of the art — those who really know the math, how to read tone, how to listen to the subtleties of clean and overdriven sounds and tones, design circuits, and understand tube behaviors. As a bonus to those who appreciate this kind of thing, we always try to throw in some interesting tweaks and tricks that are unorthodox.

The idea is to spark some interest and perhaps get more people involved in tube-based amp tone and evolution. We expect some folks to study our Upgrade Kits, learn from what we’ve done, and take off into new territory from there. No one is offended by that.

But our initial concept was to take an inexpensive stock amplifier, one that cost no more than $100 or so, and modify it into a professional- or recording-quality amp for very few bucks. The Valve Jr. was the amp that gave us the inspiration for this project. Epiphone broke the mold with their little Valve Jr. amp. Out of the box it’s a remarkable value. So, although it was a bit of a challenge I thought it was interesting because we were not stepping on anyone’s toes — we were just taking something that already existed and designing an Upgrade Kit around it. A simple proof of concept that made the case of transformers and guitar tone. It just seemed like a cool thing to do. The project was validated when pro players began demo’ing our prototype amps — they couldn’t believe how amazingly great such a tiny amp could sound, it freaked them out, and they all wanted one of their own!

Our intention was to give the kid who was practicing guitar in his bedroom, whose parents are on a limited budget, REAL guitar tone. In a typical scenario, the parents buy a cheap little amp and guitar combo because they want to see if their kid will stick with it. But the kid doesn’t understand that the sound of the amp is fatiguing. He doesn’t understand why the amp doesn’t sound good. And he doesn’t realize that the amp is fighting him, tiring him out. I know that happened to me and so many of my friends when we were kids. Struggling with hard-to-play guitars and poor-sounding amps is probably the single-most reason so many budding young (and old) guitarists give up the pursuit of their dream. But some are rescued. One day they visit a guy, or hear someone play, who has the amp with the tone and with just the sweep a few chords they experience the “My gawd!!! I want to sound like this!” phenomenon.

That is what we’re trying to offer with these Upgrade Kits — where the tone is accessible to just about anyone. So they could have an amp that wasn’t dull or desensitized. An amp that allows them to make that real connection to the tone. Tone is not just about noise and volume, it is rather complex, and undeniably emotional.

At the LA Amp Show we had our Upgraded Fender Champion “600” running into a full Marshall stack. Here we had this little amp powering eight 12″ speakers and it sounded great. People kept asking to see the back of the amp thinking that we had somehow rigged up something, but it was just the little Champ “600” with our Upgrade Kit.

When you have a nice open tone it is not about counting watts because the window is so big and wide and the soundstage is so deep that it gives you the impression of more power. We are not putting out more power with the Upgraded “600” — but it sure sounds like it! It’s about opening up that tone window and giving you more.

It’s kind of like taking a radio whose volume is set to half way and having it placed about 20 feet away from you then bring it right next to your ear — the volume has not changed but you hear a lot more of its content.

One of the things we do when modifying a circuit is to lower the noise floor, which a lot of people overlook. Many amps, like the Valve Jr., have a nasty hum in standby. We had one that would just start to howl if you left it alone for a while! So whatever high noise floor it had would eventually feedback on itself and cause that noise.

Our focus is on inspiring people. We are trying to show people that they really can get great tone today, that there is no age that has come and gone. There is still a lot of fun things left to do with your amplifier when you are on the search for great tone.

Hearing how much these Kits improve upon the tone of the amplifiers, and how well thought-out they are, will a Mercury amplifier that is designed and built by you ever make an appearance?

No. We are a supplier of key components to the boutique industry and to several of the large amplifier companies, and that is a comfortable spot to be in.

There is no shortage of amplifier companies out there and it really is a conflict of interest if we were to start selling amps and transformers. I would rather stay out of it.

The whole point of the Upgrade Kits was an area where I didn’t see any conflict with the people who were in the amplifier business. In the end the Kits really represent a transformer demonstration. If you were to just show someone a picture of a transformer or even had one in your hand and tried to explain how much better their tone would be, no one would care — it’s a yawner. But when you build one of these inexpensive Upgrade Kits and you actually hear the difference that the transformers make, it really drives home our point that transformers are important, that they are the building blocks of guitar amp tone.

And in the end we do this because we love it, we really love what we do. We get to create all of these products that help people find their tone, and who wouldn’t what to do that?

In late 2009 I had the opportunity to talk with Sergio Hamernik about the history of the Mercury Magnetics, how he became involved in making transformers for guitar amplifiers, and the difference a high quality transformer can make on your tone.

How did Mercury get its start?

The company’s roots date back to the early ’50s. Mercury was started by an old General Electrics transformer engineer who was working there pre-World War II. He then went on to do a bunch of design work for the war effort. And in the early ’50s, hung a shingle and became self-employed.

The name “Mercury” came out of his passion for Mercury cars, he always drove a Mercury since the late ’40s — he loved those cars — and eventually moved from the East Coast to the West Coast where he found that there was a lot of military and aerospace work. A booming economy in the early ’50s gave him a lot of business.

I met him in the 1970s when I was an engineering student and an audio enthusiast. Back then the electronics world was well into its solid-state “evolution,” and interest in tube gear was quickly disappearing. Not for me, however. I found myself in demand as a guy who knew about those “old things”; not only the math, formulas and specifications but I also had the “ears.” I could fix and keep the old gear running. So, I worked as a hired gun for a bunch of studio heads and pro musicians.

Typically when an amp’s output transformer blew. No one seemed to know any better so it was just swapped by whatever “factory” replacement or an off-the-shelf “equivalent” catalog transformer was handy. The invariable result was that the amp’s characteristic sound was gone. And no matter what resistors, caps or tubes were used, it could not be rescued or returned to its original sound. It was the transformers, it turned out, that were the key. The problem was coming up with a way to remedy the blown transformer replacement or repair that wouldn’t alter its tone.

To further complicate things, most transformer people I dealt with just didn’t want to bother with the music industry. For the most part the established electronics industry considered the needs and opinions of the audio and MI (Music Industry) communities as subjective, run by kooks, and occupied by people who didn’t know what they are doing. Audio and MI had always been considered the illegitimate stepchildren to the rest of the industry.

Out of pure necessity I had to got involved with transformer design and manufacture. As a customer of Mercury, they had built many custom transformers to my specifications — although we had many heated, on-going debates on the subject because the company owner hated audio! He never did understand what made guitar amp transformers tick, or how musicians thought and reacted to them.

That aside, he pestered me for almost a decade to take over the company because he felt I was the only one qualified. Eventually I did, and that was when Mercury got serious about the guitar amp connection. Sometimes you end up becoming an expert at something when no one else wants to do the job.

By the time I took the helm we were developing a really good and workable understanding of the relationship of transformer design to decent tone and how amps should behave. And around 1980 we began the long and arduous task of collecting and cataloging transformer specifications for every vintage amp, from all over the world. The deeper we dug, the more apparent it became that there were all kinds of factors that no one had previously suspected that affected guitar tone. And likewise, no one seemed to be paying attention to such things.

In turn, we invented proprietary technologies to aid this work. Even after three decades, we’re still innovating and discovering new things. From that fundamental research came our now famous ToneClone series, and later the Axiom line, which is probably the most significant advancement in toneful guitar amptransformer designs since the ’50s. Both product lines, we’re proud to say, have distinctly different niches in the annals of guitar amp tone.

We’ve not only cured the old transformer tone issues, but made it possible for musicians to upgrade their existing amps. And we’ve also made it possible for amp builders to reproduce amps of the same or better grade than even the most outstanding vintage amps of the past.

When did you become involved with making transformers for guitar amplifiers?

Back in the ’70s I worked for people on a one-to-one basis, usually under confidential arrangements, with certain rock stars that just didn’t want to be bothered by their names being flaunted around. What they want was their amps running right for recording, projects, touring, etc.

The problem was that when technicians would fix the amps they’d often loose their tone. It turned out that the culprit was the replaced output transformers. A changed output transformer would completely alter the character of the amplifier. So as I was the guy doing most of the work to resolve this issue, this expertise was brought to Mercury where we began a special division to cater to the guitar heroes.

Word got around rather quickly that Mercury was able to repair, rewind, and restore the original transformers and it just grew from there. The whole “Tone Clone” thing came from artists who had these amazing irreplaceable amps, amps that often made recording history. They didn’t want to take these amps on tour. So we came up with the innovative idea of cloning their original transformers that they’d fallen in love with. With the clones we could now easily make, for the first time ever, several identical amps for them. Or they would assign their techs to drop-in the cloned transformers so they would have, for example, six amps that would all sound the same as that first perfect amp.

These artists could now go on tour and not worry about breakdowns or theft, and keep their prized-originals back at home.

I worked with Ken Fisher, the whole Trainwreck thing, and a lot of the early boutique guys — and still do with Alexander Dumble. They preferred to keep things confidential and not let too many people know who their sources were because there were so few transformer designers that catered to the guitar amp market.

There was also a slow-but-steady dumbing-down occurring in audio and all that had been the post World War II momentum. Many of the ex-military components we’d been using were high tolerance parts, with mil-spec formulations of iron and copper and so on, that had been used to win the war effort. During the ’50s and ’60s we enjoyed the benefits of those high quality components at surplus prices. But by the late ’70s, and definitely in the ’80s, steel manufacturers started to change recipes to make the iron and other materials much more affordable.

You can hear the differences between a late ’60s Marshall, a late ’80s Marshall, and a Marshall today. A good listen will really help you to understand what changes took place. Unfortunately they made so many of those changes more out of economic considerations than anything else. The amps were loud but they seemed to be losing sight of the fact that their tone was disappearing — the “recipes” had been changed.

In addition to many other factors, the iron that Mercury uses is custom-formulated specifically for us. We buy enough of it to be able to dictate the exact recipe from the foundries. And all of our iron is literally from American ore processed right here in the USA. 100% American madeto the original specs. Are there drawbacks? Well, some of the iron rusts more easily, but that’s actually a good thing because rust is a natural insulator. But the opposite is also true. When you see a modern transformer with a silvery or a shiny core just know that they aren’t worth a damn when it comes to tone.

Can you tell us more about guitar amp transformer history?

Here’s an amusing anecdote that may help explain our case for guitar amp transformers: There’s a great deal of documentation, from back in the mid-’50s, where engineers, and other technical people, were writing really scathing reports on how awful the transformers were in the audio industry. Those darn transformers! When tubes were plugged into them there was a tendency to distort! And they couldn’t have any of that! Likewise with harmonic distortion — especially even-order harmonic distortion.

Many amp builders, techs and players, today, don’t understand that tubes were originally designed to run dead clean, linear, and be efficient voltage amplifiers. That the tone we’ve all come to know and love is caused by the transformers literally “irritating” the tubes into distortion.

Which is, of course, the whole point of what we are looking for in guitar amps. Back in the ’50s, they were fighting to get rid of those nasty distortion tonal characteristics. Now we embrace them. But that was audio – guitar amps were still in they’re infancy and yet to be realized. It took a generation or two of innovative musicians to take those “undesirable” tonal characteristics and create music; to work with distortion and make it into something musical.

Ironically, it was that no-distortion engineering mindset that ushered in solid-state, and why it was so openly embraced in the ’60s. It was solid-state electronics that eliminated the output transformer.

In the late ’60s, Vox went to Thomas Organ to have solid-state amps built. They were very proud of this state-of-the-art amplifier. Curiously, I met a few of the musicians from the late ’60s that were sponsored by, and using, those amps. The tone was so awful and unbearable that they used the enclosures but hid their old tube gear inside! As you may already be aware, the vacuum tube industry is alive and well, and we’re still waiting for the solid-state industry to catch up.

Part of the confusion is that musicians assume it’s the tubes that give them their tone. There’s a lot of synergy going on in an amp, and the tubes certainly contribute, but let me illustrate this another way. Did you know that there is what we call “output transformer-less” amplifiers in the HiFi world?

These amps basically parallel a bunch of power tubes together until they get down to 16, 8, or 4 ohms. There is no output transformer, so you literally connect the speaker directly to the tubes. If you ever get the opportunity to do an audio demo with this style of amp, you will find that while it works, it sounds nearly solid-state. The output transformer is what provokes a tube into giving the characteristics that we find desirable as far as tone. Audio engineers didn’t want the tubes to distort, as tubes are basically nothing more than very clean voltage amplifiers. But when you have a reactive element like a transformer, you irritate the tubes into harmonic distortion.

Therefore, the difference between a good and mediocre transformer is based on how it works and syncs with these tubes to produce the kind of tone or distortion we are looking for. It is not as easy as winding some wire around a steel core, if it was then we would not be having this conversation.

How does a Mercurytransformer made today compare to the transformers made in the golden age of amps (the ’50s and early ’60s)?

One of the biggest mistakes existing in today’s amplifier community, especially amongst hobbyists and do-it-yourselfers, is to blindly copy every aspect of a vintage amplifier hoping to get a piece of that golden tone. At best, this method still produces very random results. One of the key reasons for this is the often-overlooked missing transformer formula. A builder will fuss around with the tiniest of other details but completely miss how the transformers fit into the equation. In short, get the transformers right, then the rest is much easier. Here’s another look at theses deceptively simple devices:

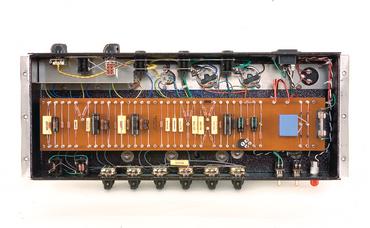

For vintage-style transformers, Mercury starts by duplicating the transformer design, build errors and all. We use the best grade components like they did in the ’50s and ’60s. We wind every layer and every turn as if it were a circuit in itself. In fact, the diagram on the left shows an output transformer circuit equivalent. Most people would think it is an audio circuit. These things are fairly complex, and all the numbers have to be right in order to get the tone we want as musicians.

For vintage-style transformers, Mercury starts by duplicating the transformer design, build errors and all. We use the best grade components like they did in the ’50s and ’60s. We wind every layer and every turn as if it were a circuit in itself. In fact, the diagram on the left shows an output transformer circuit equivalent. Most people would think it is an audio circuit. These things are fairly complex, and all the numbers have to be right in order to get the tone we want as musicians.

We really do follow the recipe to a point. Although we don’t repeat any of the mistakes or inconsistencies that were prevalent, but didn’t affect tone. For example, if you were into Fender tweeds or late-’60s Marshalls. To do this we would literally put the word out to rent or borrow dozens of amplifiers to find the one or two that had thesound, and dismiss the rest. There were typically many inconsistencies as well as “happy accidents” in the best-sounding examples we’ve auditioned. A lot of this has to do with the sloppy tolerances of the original transformers.

For our transformers we extract the best parts and virtues of the original best-of-breed transformers and remove all of the obstacles to tone. Perhaps just as important is that we adopted a “cost is no object” approach, making our transformers equal or better than the originals — and then add consistency. We now have this so finely tuned that if you bought a transformer from us five years ago, and then the same one today, it would sound exactly the same. You don’t want good batches and bad batches, which is precisely what made the original production runs vary so much.

Another issue is the so-called controversy between paper tubes and nylon bobbins. In the vintage years they used both. Some people think that somehow, some magical quality comes from using a paper tube winding form over a nylon bobbin. Tonally it made no difference at all. Paper tubes were widely out of tolerance most of the time because of how they were made. They would wind multiple coils on long sticks then use a saw or blade to cut off the various coils. In order for these long tubes or coils to come off of their winding forms they had to be conical. So this invariably meant that the first coil would be larger in diameter and the last coils smaller. As you can see, it’s easy to see why each of these inconsistently-made bobbins had a greater difference than the material they were made from. And there are other issues that occur over time, like paper has a tendency to disintegrate, collect moisture, etc.

When we switched to using nylon bobbins the tolerances were within 3,000’s of an inch of each other, as opposed to the wildly varying amounts found in paper tubes. If you were ever to take apart a really old transformer (pre-’70s) sometimes you’ll find wood wedges that are jammed between the paper tube and the core because that piece of paper was too wide and too sloppy to fit into the core correctly! They would force a wedge in there so the darn things wouldn’t rattle!

Which method, paper or nylon, made for the best tone? It’s the luck of the draw. We’re fortunate in that we have all these stars as clients who have these amazing-sounding amps. They went through the hassle of culling and choosing and picking the special amps that inspired them. The amps they recorded with. When we analyzed their transformers we sometimes found happy accidents or other little anomalies that would set a transformer apart from already sloppy tolerances of the standard production run.

There are little subtleties and changes from one transformer to another that make a heck of a difference tonally. So when you look online at our list of ToneClones, just know that they are from the hand-picked, best-of-the-best amps of their model and era. We continue this “weeding” process every day — and there’s apparently no end in sight. And that’s why, with some amps, we have several versions — each with its own tonal qualities — and others only a single set to choose from.

We use this process to establish new benchmarks. And you never know, tomorrow a new variant may arrive that totally blows away what we already thought was as good as it could ever get.

It is interesting that you take that approach to upgrading — the never-ending search for better-sounding benchmarks.

There is no real money or glamour in what we do, it is really all born of a passion for music. I come from a musical family, my Mom taught me as a little kid that music was a form of “food.” And that hasn’t changed. Everyone who works at Mercury is just in love with playing and listening to music, and we all believe that there is always some room for improvement or a way to raise the bar somehow.

Back in the ’70s and ’80s there wasn’t really a need for a company that designed and sold transformers to the public, so I stayed away from the general public for as long as I could and really only worked with professionals.

But at some point I realized that it was the average player who was getting ripped-off. Things were getting dumbed-down, the tone is slowly and steadily being vacuumed out of the amps. They were becoming duller-sounding, less interesting and more noisy. So, we decided to formally launch this product line so the average guy could have access to our technology. It takes an extreme amount of labor and effort it takes to build them to this standard. You know, even if someone wanted to buy 1000 transformers we would have to no-bid them because we really don’t have any way of doing things quickly.

Automation isn’t a practical solution. Everything we do is wound by hand, one at a time; it is the only way it can be done. Say you have 100 turns and 10 layers, well that would mean 10 turns per layer — that is how a machine would think of it. But what if a rock legend’s best transformer was 9 turns on one layer, 11 turns on the next, 7 on the next, 3 after that and so on, but the sum total ended up being 100 turns. Sometimes one layer can have a different winding style than the other; sometimes it is non-symmetrical meaning, if it is a push-pull, that one side of the primary doesn’t have the same turns as the other side. If that was the recipe that created the magic, we’d have to duplicate it. It’s just not practical to build machines to do that, so we end up having to do it by hand. It’s the proud old-school craftsmanship way of doing things. Something I think we could see a lot more these days.

We have a reputation for nailing tone. Our Fender transformers don’t sound like Marshalls, they sound like Fenders — and vice versa. In fact, we’ve become the industry’s new standard. If you were going to design or create a tube-based amp, it’s clear that we’re the folks to talk to.

Can you explain how a Mercurytransformer can improve an amplifier’s tone and how they outperform the stock transformers found in most amplifiers?

In designing toneful transformers specifically for guitars (and that’s all we’re talking about here, not necessarily transformers for HiFi or any other purpose), the trick is in the magnetic field and how it behaves. The nature and the speed with which the iron reacts to the changing of an alternating current, in an alternating magnetic field, is what makes tone happen.

If you have “slow” iron, you’ll have a dull, non-sparkly sound with no bell tones — no matter what you do with the amp it will always be kind of noisy and fuzzy.

Where others have tried and failed they’ve blindly followed generic transformer formulas without understanding that guitar amps are different animals. They’ve somehow missed that point despite all the evidence to the contrary. The fact is that transformers for guitar amps do not necessarily follow textbook rules.

Indeed, it should probably be noted that we’ve developed a whole new technology around transformer design specifically, and only for the guitar industry. And that these designs are essentially irrelevant to any other use. But Mercury is also in a highly unusual position. Our decades of transformer “vivisection” have revealed all manner of unconventional tips ‘n tricks to us. And we’re now the keepers of this new, but proprietary, technology.

I seriously doubt that we could have done it without the, let’s call it “archeological benefits,” of our observations. Decades of studying the good, the bad and the ugly of guitar amp transformers have revealed a great deal.

Nothing that I have found in the reissue market, transformer-wise, even resembles anything that was made during the “the golden age of tone.” They are unrelated. The inductance, magnetic fields — all of that is just completely different and far removed from the original designs and recipes. So there is no way that a reissue amp is ever going to sound vintage unless they bother putting in the right ingredients.

With our Upgrade Kits, for example we’re trying to show people that we can move forward into new sonic territory from where vintage designs and tone left off. And our Axiom series transformers are the definitive showcase for this technology. Their tone is just amazing.

To push the point even further, we don’t include any “voodoo” parts in our Upgrade Kits. With the exception of the transformers, the Kits use only common, everyday, and off-the-shelf components. And most of our Kits also include a Mini-Choke. When the circuitry is correctly designed a Mini-Choke will make a huge improvement in an amp’s tone because, in terms of its power supply, it changes the way the amp works.

A good guitar amp is only as good as its power supply. If you have a dynamic and moving power supply that reacts to the demands of the audio end you’ll get get great note separation and good bass dynamics. You start to hear chimes and other phenomenon, and even the harmonics between the strings like a “5th note.” What the heck is the “5th note”? In barbershop quartets, if they get their harmonies right, they hear the “5th note” which is basically a harmonic of all four singers. We are doing that with our guitars thanks to distorted amplifiers.

Where did the idea for offering an Upgrade Kit for amplifiers like the Champ “600” and Valve Jr. come from and who designed the Upgrade?

I designed all of the magnetics (the transformersandMini-Choke) and the general concept behind the Upgrade in league with Allen Cyr from the Amp Exchange. He is one of the most competent, finest amp designers I know of; there are only about five in the world that are true masters of the art — those who really know the math, how to read tone, how to listen to the subtleties of clean and overdriven sounds and tones, design circuits, and understand tube behaviors. As a bonus to those who appreciate this kind of thing, we always try to throw in some interesting tweaks and tricks that are unorthodox.

I designed all of the magnetics (the transformersandMini-Choke) and the general concept behind the Upgrade in league with Allen Cyr from the Amp Exchange. He is one of the most competent, finest amp designers I know of; there are only about five in the world that are true masters of the art — those who really know the math, how to read tone, how to listen to the subtleties of clean and overdriven sounds and tones, design circuits, and understand tube behaviors. As a bonus to those who appreciate this kind of thing, we always try to throw in some interesting tweaks and tricks that are unorthodox.

The idea is to spark some interest and perhaps get more people involved in tube-based amp tone and evolution. We expect some folks to study our Upgrade Kits, learn from what we’ve done, and take off into new territory from there. No one is offended by that.

But our initial concept was to take an inexpensive stock amplifier, one that cost no more than $100 or so, and modify it into a professional- or recording-quality amp for very few bucks. The Valve Jr. was the amp that gave us the inspiration for this project. Epiphone broke the mold with their little Valve Jr. amp. Out of the box it’s a remarkable value. So, although it was a bit of a challenge I thought it was interesting because we were not stepping on anyone’s toes — we were just taking something that already existed and designing an Upgrade Kit around it. A simple proof of concept that made the case of transformers and guitar tone. It just seemed like a cool thing to do. The project was validated when pro players began demo’ing our prototype amps — they couldn’t believe how amazingly great such a tiny amp could sound, it freaked them out, and they all wanted one of their own!

Our intention was to give the kid who was practicing guitar in his bedroom, whose parents are on a limited budget, REAL guitar tone. In a typical scenario, the parents buy a cheap little amp and guitar combo because they want to see if their kid will stick with it. But the kid doesn’t understand that the sound of the amp is fatiguing. He doesn’t understand why the amp doesn’t sound good. And he doesn’t realize that the amp is fighting him, tiring him out. I know that happened to me and so many of my friends when we were kids. Struggling with hard-to-play guitars and poor-sounding amps is probably the single-most reason so many budding young (and old) guitarists give up the pursuit of their dream. But some are rescued. One day they visit a guy, or hear someone play, who has the amp with the tone and with just the sweep a few chords they experience the “My gawd!!! I want to sound like this!” phenomenon.

That is what we’re trying to offer with these Upgrade Kits — where thetone is accessible to just about anyone. So they could have an amp that wasn’t dull or desensitized. An amp that allows them to make that real connection to the tone. Tone is not just about noise and volume, it is rather complex, and undeniably emotional.

At the LA Amp Show we had our Upgraded Fender Champion “600” running into a full Marshall stack. Here we had this little amp powering eight 12″ speakers and it sounded great. People kept asking to see the back of the amp thinking that we had somehow rigged up something, but it was just the little Champ “600” with our Upgrade Kit.

At the LA Amp Show we had our Upgraded Fender Champion “600” running into a full Marshall stack. Here we had this little amp powering eight 12″ speakers and it sounded great. People kept asking to see the back of the amp thinking that we had somehow rigged up something, but it was just the little Champ “600” with our Upgrade Kit.

When you have a nice open tone it is not about counting watts because the window is so big and wide and the soundstage is so deep that it gives you the impression of more power. We are not putting out more power with the Upgraded “600” — but it sure sounds like it! It’s about opening up that tone window and giving you more.

It’s kind of like taking a radio whose volume is set to half way and having it placed about 20 feet away from you then bring it right next to your ear — the volume has not changed but you hear a lot more of its content.

One of the things we do when modifying a circuit is to lower the noise floor, which a lot of people overlook. Many amps, like the Valve Jr., have a nasty hum in standby. We had one that would just start to howl if you left it alone for a while! So whatever high noise floor it had would eventually feedback on itself and cause that noise.

Our focus is on inspiring people. We are trying to show people that they really can get great tone today, that there is no age that has come and gone. There is still a lot of fun things left to do with your amplifier when you are on the search for great tone.

Hearing how much these Kits improve upon the tone of the amplifiers, and how well thought-out they are, will a Mercury amplifier that is designed and built by you ever make an appearance?

No. We are a supplier of key components to the boutique industry and to several of the large amplifier companies, and that is a comfortable spot to be in.

There is no shortage of amplifier companies out there and it really is a conflict of interest if we were to start selling amps and transformers. I would rather stay out of it.

The whole point of the Upgrade Kits was an area where I didn’t see any conflict with the people who were in the amplifier business. In the end the Kits really represent a transformer demonstration. If you were to just show someone a picture of a transformer or even had one in your hand and tried to explain how much better their tone would be, no one would care — it’s a yawner. But when you build one of these inexpensive Upgrade Kits and you actually hear the difference that the transformers make, it really drives home our point that transformers are important, that they are the building blocks of guitar amp tone.

And in the end we do this because we love it, we really love what we do. We get to create all of these products that help people find their tone, and who wouldn’t what to do that?

Source: https://mercurymagnetics.com/pages/news/GuitarFixation/SHinterview/index.htm

We always maintain a steady flow of gear arriving for review, but sometimes we also employ a fascinating if time-consuming research strategy that involves logging onto eBay, picking a broad category such as “guitar amplifiers,” and settling in for as long as it takes to patiently scroll through every page of listings. Yeah, that’s often 50 pages or more, but since we can’t possibly think of all the items that might interest us and search for them by name, it’s far more revealing and productive to just hunker down and scroll. Rarely do we fail to find something intriguing that would have otherwise been missed, and such was the case on a morning in August when we stumbled on a listing for a 1959 tweed Deluxe. Were we looking for a tweed Deluxe? Nope. Wouldn’t have crossed our mind at the time…. We had already reviewed 5E3 reproductions from Fender, Clark and Louis Electric within the past 3 years, and we have frequently referenced our 1958 Tremolux as being our desert island #1. Isn’t a Tremolux just a tweed Deluxe with tremolo in a bigger box? No… not even close. That would be like saying you wanted to date a blonde – any blonde. For the record, our fixed bias Tremolux possesses a cleaner tone with a bigger, booming voice created by the taller Pro cabinet. The Two Fifty Nine is a completely different animal….

Sporting a February 1959 date code on the tube chart, the ’59 had been listed by a seller in Arkansas who turned out to be Tut Campbell, formerly a well-known guitar dealer in Atlanta. Still buying and selling gear, Campbell had described the Deluxe as being in original condition with the exception of a replace output transformer – a big old mono block Stancor dating to 1957. Given the otherwise original condition of the Deluxe, which included the Jensen P12R, we made Campbell a “best off” below his asking price and scored the amp for $1,850 shipped. We wouldn’t say we stole the Deluxe, but it seemed a fair price of admission for the opportunity to experience and explore still another rare classic and supremely worthy piece of Fender history on your behalf.

The Deluxe arrived with the big Stancor dangling from the chassis despite Campbell’s careful packaging. Wasn’t his fault, really – in a feeble effort to avoid any additional holes being drilled in the chassis, the fellow who installed the Stancor in the ’60s had merely tightened set screws over the small tabs at the base of the heavy tranny, which was designed to be mounted upright – not hanging upside down in a guitar amplifier. Of more concern was the fact that while the amp was lighting up, there was no sound…. Well, we’ve been here before, so we made a call to God’s Country and the Columbus, Indiana domicile of Terry Dobbs – Mr. Valco to you. We had already set aside a spare output transformer (Lenco, McHenry, IL) that had been the original replacement installed in our ’58 Tremolux when we first received it, replaced with a Mercury Magneticsfor our June ’07 review article. Mr. Valco cheerfully answered his phone and as we explained the situation with the Deluxe he agreed to walk us through the installation of the new replacement – a simple process involving four lead wires being connected to the rectifier and output tube sockets, and the speaker jack. As long as you put the correct wires in the right place, a piece of cake, and we had the new tranny in within 10 minutes. Pilot lamp and all tubes glowing, still no sound…. Valco patiently guided us through a series of diagnostics with the multi-meter and the Deluxe was running on all cylinders, pumping 380 volts. Stumped, and with the hour growing late, we called it a day. Leaving the mysteriously neutered Deluxe chassis on the bench until tomorrow.

Morning came with a whining voice delivering a plaintive wake up call – “It’s got to be something stupid and simple….” Inspired by a huge steaming mug of Jamaican High Mountain meth, we sat back down at the bench, tilted the innards of the Deluxe chassis forward beneath a bright halogen desk lamp and peered in for answers. We began slowly examining the chassis in sections, looking for broken or dull solder joints, loose or broken wires, while gently pushing and prodding wires and connections with the eraser tip of a #2 pencil as we had seen Jeff Bakos do so often at his bench. After ten minutes or so we were about to give up, when we turned our attention to several places where the circuit was grounded to the chassis adjacent to the volume and tone pots, and damned if a solder joint for one of the uninsulated ground wires hadn’t separated from the chassis. No ground, no sound, and as soon as we had restored the solder joint the Two Fifty Nine arose from the dead with a mighty A major roar.

The amp was indeed remarkably well-preserved in all respects, with the typical amber patina of old tweed. The burnished chrome control panel remained bright and clean with no corrosion, the original handle remained intact, and a couple of small ciggie burns on the edge of the cabinet added a stamp of historic legitimacy to the Deluxe’s pedigree. The top half of the Jensen’s frame was coated in a fine film of red clay dust from the Delta, and while the cone was in remarkably good shape with no tears, an audible voice coil rub called for a recone. We would send the speaker to Tom Colvin’s Speaker Workshop in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, requesting that he leave the original unbroken solder joints for the speaker wires intact if possible.

Meanwhile the first order of business was to listen to an assortment of NOS tubes from our stash, and audition no less than a half dozen speakers. Different sets of power tubes and individual preamp tubes will sound surprisingly different, so we started out with a matched pair of NOS RCA 6V6s, a GE 5Y3 rectifier, and an RCA 12AX7 and 12AY7. From there we subbed in a dozen different RCA, Amperex, Tesla and GE 12AX7s, noting varying levels of brightness, warmth and intensity among them all. For an edgier, more aggressive voice, the GEs and Amperex typically deliver the goods, while RCAs produce a slightly warmer, richer, fuller tone. We also experimented with a 12AT7 and 12AX7 in place of the lower gain 12AY7, and while those tubes ramp up gain and distortion faster and with more intensity than the 12AY7, they seemed like overkill for us. Our Deluxe possesses a tone of gain using the stock 12AY7.

Rather than repeatedly reloading the Deluxe with different speakers, we used a Bob Burt 1×12 cabinet built from 100-year-old pine for our speaker tests. The original Jensen had never been pulled from our amp, but multiple speaker replacements in an old Fender inevitably cause the speaker mounting screws to loosen in the baffleboard, making speaker swaps unnecessarily clumsy and complicated. When we do run into loose mounting screws, we simply run a few small drops of Super Glue around the base of the screw and surrounding wood. Allow to dry and your screws will stay put provided that you don’t torque the nuts on the mounting screws like an idiot with a socket wrench. Don’t be that guy,

We tested a range of speakers that included a Celestion G12H 70thAnniversary, Colvin-reconed ’64 Jensen C12N, Eminence Wizard, Private Jack, Alnico Red Fang, Teas Heat, Screaming Eagle, Red, White & Blues, and Warehouse Green Beret, Veteran 30, Alnico Blackhawk and Alnico Black & Blue. The Alnico speakers generally produce a tighter, smoother, slightly more compressed tone, with a variable emphasis on upper mid-range and treble frequencies, while the speakers with ceramic magnets possess a wider, more open sound. Higher power ratings of 75W-100W offered by the Red, White & Blues, Screaming Eagle and Warehouse Blackhawk typically translate into more graceful handling of bass frequencies, and in a 20 watt Deluxe, zero speaker distortion, for a clean, powerful voice.

Let’s cut to the chase with speaker evaluations, shall we? It has become clear to us that even after reviewing a dozen speakers in as much detail as mere words allow in a single article, many of you remain uncertain about which speaker to choose. No kidding. We would absolutely love to hand you a single magic bullet when it comes to speaker swaps, but here’s the dirty little secret about choosing speakers…. The overall character of the amp you will be installing your new speaker in is critical, and to some extent, the type of guitars and pickups you play most often are important, too. Tailoring your sound with the unique gear you play is not a one-size fits-all proposition – you have to invest some thought into the process. Are you going for a classic “scooped” American Fendery tone, or something more British, with a bit of an aggressive edge and upper midrange voice? Are you playing guitars with single coil pickups or humbuckers? Is there a specific, signature tone you are searching for, or are you playing a wide variety of musical styles that requires a broader range of tones? Do you like the more open sound of speakers with ceramic magnets, or the smoother compression of Alnico? What are you not hearing from your amp and the speaker that’s in it now? Do you want a brighter tone, darker, better bass response, or fuller, more prominent mids? Do you want to really drive the speaker and hear it contributing to the overdriven sound of your amp, or do you want a big, clean tone with no speaker distortion in the mix? The truth is, if you don’t know what you want, you are far less likely to get it. On the other hand, nothing is accomplished with paralysis by analysis. To be perfectly honest, there are lots of speakers made by Celestion, Eminence, Warehouse and, if you can wait long enough for them to break in, Jensen, that we could and would be perfectly happy with, but we would also choose them carefully, taking into account all the factors mentioned above. After a couple of days spent swapping speakers, we ultimately concluded that we preferred the ’64 C12N for a classic tweed Deluxe tone, and a broken-in Celestion G12H 70th Anniversary for the most mind-altering 18 watt Marshall tone we have ever heard. Seriously. More on that in a minute….

Having split more than a few hairs with our speaker swaps, it was time to start picking nits off of gnats with some output transformer evaluations. We first contacted Dave Allen of Allen Amplification, who also stocks Heyboer transformers built to his specs. We found a variety of appropriate output transformers on Allen’s site that offered subtle variations on a stock original Deluxe OT, and we asked Dave to describe the TO26 model we wished to try in the Deluxe: